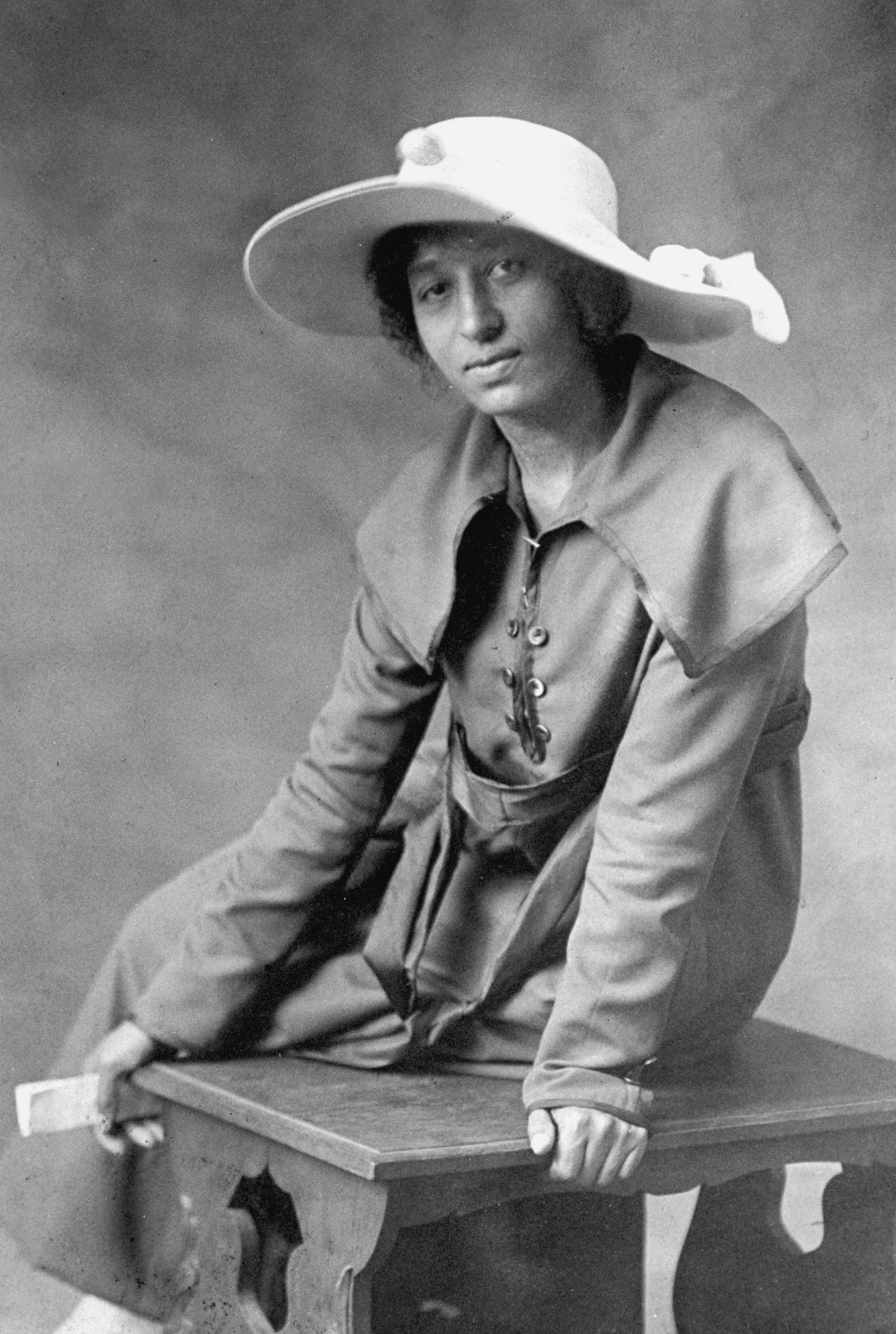

Unidentified young woman, ca. 1915–25. (Courtesy of Norton / Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America)

L ike so many problems in contemporary scholarship, the archive obsesses even as it disappoints. The latter feeling feeds the former: we may never be done imagining new ways to coax the past’s full truth from its partial traces, to buff opaque artifacts until history shines through. Sometimes the archive is an abstraction in need of theorizing, the call you place eagerly, connection spotty and crackling with static, to the unresponsive dead. For the practicing researcher, the archive is more often a particular room of variable grandeur, in which particular boxes are carted out by variably accommodating librarians. You pull particular files and puzzle over variably decipherable script. If you’re lucky, you see something—or see something through it. You get absorbed. 1

By Saidiya Hartman

Both obsession and disappointment are magnified for scholars of the subjugated or the dispossessed. For theorists, conceptual problems proliferate: how to listen for the dominated in the archives of the dominant? How, for example, might one recover the experiences of enslaved people—barred from literacy on threat of torture, sale, or death—from the records of owners and traders without amplifying the violence that confined them there? In her 2008 essay, “Venus in Two Acts,” Saidiya Hartman attempts to exhume one black woman called Venus, killed aboard a slave ship, from the paper trail of the Middle Passage. Of the materials that constitute that trail, she writes, “The archive is, in this case, a death sentence, a tomb, a display of the violated body, an inventory of property, a medical treatise on gonorrhea, a few lines about a whore’s life, an asterisk in the grand narrative of history.” The scholar’s route to a different narrative is riddled with obstacles; her sources are alternately too scant and too extensive. The absence of personal testimony isn’t compensated for but rather compounded by reams of documentation: bills of sale, court transcripts, ship manifests, newspaper clippings, and so on. Consulting these archives can feel like staring into a dense void. 2

Or so I’ve learned from reading Hartman, a professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University. For the past two decades, she has been among our foremost archival thinkers. As a theorist, researcher, and writer, her impact has been enormous, her model formidable and enabling. Hartman’s first two books found new angles of approach to Transatlantic slavery and what she terms its “afterlife”—the “skewed life chances, limited access to health and education, premature death, incarceration, and impoverishment” that persist into our present. Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America (1997) traced “tragic continuities” between the routine violence of enslavement and racist forms of discipline that emerged after Emancipation. Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route (2007) broke from the protocols of scholarly writing, blending memoir with narrative history to interrogate how the epochal ruptures of the slave trade still strain relations between contemporary Africans and black Americans. Through its account of Hartman’s own trip to Ghana, Lose Your Mother folded the research process into the stories it yields. 3

H artman’s revelatory new book, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments, responds to another archival disappointment—a lingering gap in the story of slavery’s afterlife. Curious about the everyday experiences of urban black women at the turn of the 20th century, Hartman went in search of “photographs unequivocal in their representation of what it meant to live free for the second and third generations born after the official end of slavery.” She looked for “the beauty and possibility” that she imagined such women to have cultivated in defiance of poverty, policing, and the proscriptions of progressive reformers. Instead, she found “visual clichés of damnation and salvation,” thousands of images of supposed profligacy and slum privation, punctuated by the occasional good example of modest two-parent households. The textual archive proved comparably distorted. From the 1890s through the 1920s, ordinary black women only seemed to make it into print when marked as a social problem: morally lax, suspected of prostitution, averse to work, indifferent to authority, and a lure and a threat to white lovers, audiences, and voyeurs. 4

Missing from these documents were the wayward lives and beautiful experiments of Hartman’s title. From the archive’s scraps and shards, Wayward Lives assembles a sprawling cohort of “sexual modernists, free lovers, radicals, and anarchists.” In the increasingly segregated cities of the northern United States, black women’s efforts to not simply subsist but also claim pleasure required imagination as well as resourcefulness; their creativity found expression in cabarets and theaters as well as in the new intimacies of city life. The book’s broad sweep, and its nimble pivoting among a range of scales and perspectives, make room for anonymous loiterers and recalcitrant inmates alongside fleeting stars and the more enduringly famous: Billie Holiday appears briefly as 14-year-old Elinora Harris, lying to police about her age and name in order to avoid a long custodial sentence, and W. E. B. Du Bois is reanimated as a young and self-doubting sociologist, sent to study Philadelphia’s “emergent ghetto” as it took shape in the 1890s. These known figures brush shoulders in Wayward Lives with the unexceptional and the unnamed. 5

William Gottlieb’s ‘Portrait of Billie Holiday and Mister’ in Downbeat, New York, 1947. (Courtesy of Norton / Library of Congress)

For most of Hartman’s subjects, desire and constraint foreclosed the nuclear family. Employment discrimination, residential segregation, and uneven patterns of migration and policing made black northerners sexual and gender dissidents by necessity: “unwed mothers raising children; same-sex households; female breadwinners; families composed of siblings, aunts and children;” and other forms of “elastic kinship” disturbed race leaders like Du Bois, but Hartman reconceives them as “a resource of black survival, a practice that documented the generosity and mutuality of the poor.” Young women became a particularly charged locus of white anxiety about black kinship, and their sexuality was fretted over as a moral barometer of the race. 6

Concern alternately masked and manifested itself as violence. Status offenses and “wayward minor laws” made young black women uniquely vulnerable to criminalization. “Serial lovers, a style of comportment, a lapse in judgment, a failure of restraint, an excess of desire—these were not crimes in and of themselves, but indications of impaired will and future crime. ” The subjective nature of these offenses gave police officers carte blanche to terrorize black women and gave judges discretionary power to punish them preemptively. Inviting a man into your home, quitting a degrading job, or simply standing alone on the sidewalk might all be grounds for arrest and confinement. In a world this punishing, to pursue beauty, plot a future, or flout propriety was to openly revolt against unrelenting, state-sanctioned antagonism. The forms of intimacy that provoked so much meddling from progressive reformers assume, in Hartman’s narration, an insurgent power and a “utopian” cast. Sexual and domestic experiments represent nothing less than a “collective endeavor to live free.” 7

Under the unremitting pressures of the city, young black women inaugurated modernity—“before Gatsby,” before blues singers like Bessie Smith were captured on phonograph, and before Alain Locke heralded a “New Negro” in the arts. Wayward Lives envisions these rebellious women on every street corner and in every tenement hallway of New York and Philadelphia’s growing black neighborhoods, beginning in the late 19th century. But like the enslaved subjects of Hartman’s previous books, few of these women’s voices survive unfiltered: the author instead finds her protagonists marveled at, worried over, denounced, and sporadically quoted in reformatory case files, court documents, sociological surveys, news stories, and memoirs of moral crusaders. Against such effacements, to describe young black women’s everyday experiments would be achievement enough. In moving homage to her characters, Hartman takes a bigger risk. Wayward Lives is thrilling to read because it invents a genre as deft and adventurous as the lives it chronicles. 8

H artman’s 2008 essay, “Venus in Two Acts,” concluded by proposing an approach called “critical fabulation,” through which a researcher might use narrative to respond creatively to archival omissions, struggling “both to tell an impossible story and to amplify the impossibility of its telling.” That essay’s tantalizingly brief experiment in storytelling was riven by doubt, qualification, and cautious respect for “what cannot be known.” The narratives of Wayward Lives are deeply researched, but in her new book Hartman seems to have shed any inhibiting circumspection regarding the archive’s limits. Her writing remains unfailingly self-reflexive: she makes ample use of the first- and second-person, training readers in her own habits of thought—the first chapter begins, “You can find her in the group of beautiful thugs and too fast girls congregating on the corner and humming the latest rag.” Hartman likewise poses many questions that are left unanswered, confessing the gaps in her sources. But she also authorizes herself to fill them with her own speculations about her protagonists’ most private fears and preciously guarded desires. In the book’s gorgeous opening statement of method, critical fabulation blossoms into “close narration, a style which places the voice of narrator and character in inseparable relation, so that the vision, language, and rhythms of the wayward shape and arrange the text.” 9

The resulting prose is incantatory, often making its way forward by amendment and accretion. Clauses cascade across the page, strung together loosely with comma after comma. Some passages read like fiction that’s been overlaid with a historian’s annotations and interpretive asides. Others read like poetry. This verbal splendor befits Hartman’s subject. “In the slum, everything is in short supply except sensation,” she remarks early on. “The experience is too much. ” Most chapters track a protagonist’s movement through the noisy landscape of the city, accumulating an ever-larger cast as friends, lovers, and assailants cross or impede her path. Fifteen-year-old Mattie Nelson leaves Virginia for New York with indefinite dreams of “something else;” Esther Brown abandons her job as a live-in domestic for the relative freedom of subsistence in Harlem among friends; Eva Perkins is waylaid by police in the doorway of her own apartment. All three women partake of “the general unrest that came to define the age,” and all end up in the abusive Reformatory for Women at Bedford Hills. Key terms recur throughout: errant, ensemble, anarchy, beauty, riot, flight, refusal, enclosure. 10

As the forked paths of the possible multiply freely, portraits already stuffed with sensuous fact become yet more richly detailed. Young black women embraced chance, danger, and unforeseen consequences in pursuit of more viable and beautiful lives, but readers need not take Hartman’s word for it. We experience that openness for ourselves when she enumerates all the versions of what might have been, all the feelings and ambitions that eluded archival capture. Consider, for example, one of the book’s many portraits of an artist at work, from the story of aspiring actress Edna Thomas: 11

The freedom of being less like Edna and more like others was exhilarating. To be lost to the world of marriage and duty and disappointment and tedium as she entered the space of the ensemble and the intensity of creating and inhabiting a world with others, a domain of collective bodies, kinesthetic experience and gestural language. All other roles had to be relinquished. The stage enabled her to escape her paltry individual life and slip into someone else’s existence—prostitute, queen, toiling laborer, flawed heroine—and to shed every petty concern. 12

The chapter opens with the rape of Edna’s mother at age 12 by a man whose family had owned her great-grandmother; it ends with Edna’s decades-long romance with the English aristocrat Lady Olivia Wyndham. Hartman acknowledges that Edna was “one of the lucky ones,” but her white lover is no Pygmalion. Edna escapes violence and poverty not by transcending her environment or submitting to moral reform, but rather by making an art of her “world with others.” 13

M uch of the energy and tension of Hartman’s writing derives from the line her subjects walk between anomaly and exemplar, between “rare bird” and face in the crowd—the line, that is, between the possible and the probable, between freedom and enclosure. Edna Thomas’s trajectory is astonishing, but her chapter’s final paragraph submerges her back into the mass of black women whose “urge for expression” was fierce but (unlike Edna’s) lacked a sanctioned outlet: “Everywhere you looked you could find it.” By the end of Wayward Lives, the anonymous chorus girl, or “chorine,” stands out as Hartman’s favorite liminal figure, emerging from and receding back into collectivity. “Dancing and singing fueled the radical hope of living otherwise,” Hartman writes, in one of many variations on a theme, “and in this way, choreography was just another kind of movement for freedom, another opportunity to escape service, another elaboration of the general strike.” Filling the stage behind or between marquee performers, the chorus achieves ecstatic expression amid great constraint. The chorine isn’t the star and likely never will be, yet she gives the show its texture, depth, dynamism, volume. In the right lighting and with the right moves, “The chorus threatened to steal the show.” 14

As a culminating archetype, the chorine makes a canny answer to the composites bequeathed by Hartman’s sources, in which black women are lumped together and presumed interchangeable by reporters, social workers, and the state. Hartman’s contest with these authorities over her characters’ stories is also a contest over the tones and genres in which they’re told: she therefore cedes “the impoverished realm of realism” to the judges and reformers whose records she combs, with their moralizing demands to tone it down, learn some discipline, and be reasonable. Her “close narration” instead takes its cues from more flagrantly imaginative genres, like fiction and performance. (The chorus girl, in particular, leads Hartman to early black cinema and theater.) 15

But the chorus girl’s role is more significant than mere rejoinder, her promise not defined in reaction to the experts that plague her. Her dancing links the experiments in pleasure and survival that populate Hartman’s narratives; her choreography is a rehearsal for remaining ungovernable: “Tumult, upheaval, flight—it was the articulation of living free, or at the very least trying to.” Like Hartman’s own prose, the chorus’s blend of coordinated and improvised movement, of individual expression and collective purpose, accommodates characters both representative and unprecedented, exemplary and sui generis, symptomatic and self-made. A chorine may do domestic work by day, and the chorus is her reprieve; she may long for a leading role, and the chorus is her purgatory; she may be ambitionless and bored, and the chorus is just where she finds herself right now. None of these women have been recognized as protagonists of history. In their own time, they were “beneath the scrutiny” even of race leaders and socialists, who effectively abandoned the chorine to the archives from which Hartman has retrieved her. In Wayward Lives , we learn to see her as an icon of unflagging motion, collaboration, and willed anonymity—an artist whose own life was her medium. “She is an average chorine, just one of the girls, nobody special, part of the assembly, engulfed in the crowd, lost in the company of minor figures.” With all that she performs, the stars aren’t missed. 16

What’s at stake this November is the future of our democracy. Yet Nation readers know the fight for justice, equity, and peace doesn’t stop in November. Change doesn’t happen overnight. We need sustained, fearless journalism to advocate for bold ideas, expose corruption, defend our democracy, secure our bodily rights, promote peace, and protect the environment.

This month, we’re calling on you to give a monthly donation to support The Nation’s independent journalism. If you’ve read this far, I know you value our journalism that speaks truth to power in a way corporate-owned media never can. The most effective way to support The Nation is by becoming a monthly donor; this will provide us with a reliable funding base.

In the coming months, our writers will be working to bring you what you need to know—from John Nichols on the election, Elie Mystal on justice and injustice, Chris Lehmann’s reporting from inside the beltway, Joan Walsh with insightful political analysis, Jeet Heer’s crackling wit, and Amy Littlefield on the front lines of the fight for abortion access. For as little as $10 a month, you can empower our dedicated writers, editors, and fact checkers to report deeply on the most critical issues of our day.

Set up a monthly recurring donation today and join the committed community of readers who make our journalism possible for the long haul. For nearly 160 years, The Nation has stood for truth and justice—can you help us thrive for 160 more?

Onwards,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation

Sam Huber Sam Huber is a writer and senior editor at The Yale Review.